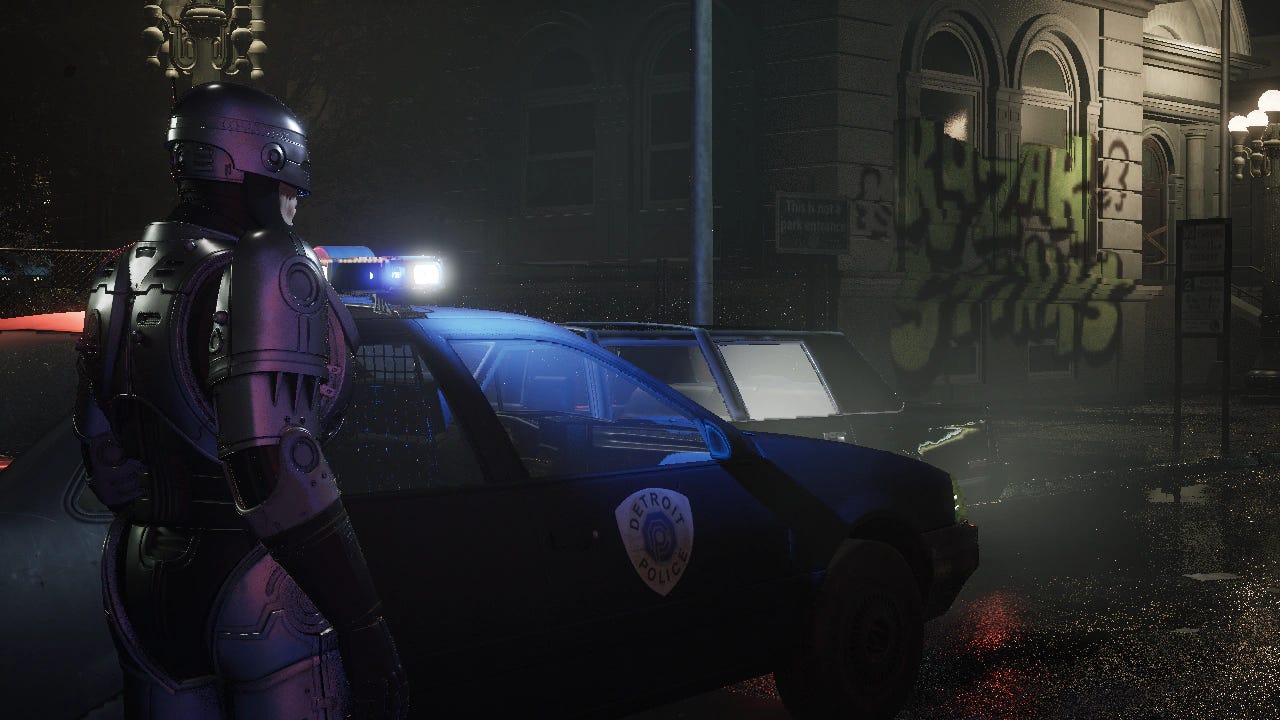

Robocop: Rogue City - Street justice with a dash of empathy

Robocop with a heart.

In Rogue City (Detroit) you can be judge and executioner, or Robocop (or close enough to Judge Dredd). You execute criminal punks with total prejudice and pursue their leaders with lawful abandon.

But you also solve murder mysteries, cases of public disturbance, issue parking tickets. You have honest conversations with people who need it or care about you, and even save a cat.

Rogue City is close to a masterpiece of gameplay, and a masterclass on mixing action with lateral design. It stays true to the satire of its source material, via excellent writing and lite immersive-sim elements, superbly paced between brutality and empathy.

Wholesome level: low to good. It's a violent game. It deals with crime, poverty, greed, but has heartfelt moments of connection and humanity.

Greetings from Detroit (wish you were here?)

To address the obvious, Rogue City is a violent game. It's the kind of adventure you enjoy if you're a Robocop or action fan. But - a considerable but - it's much more, an honest attempt to understand Robocop (Murphy) and build a context where he'll exercise both violence and humanity.

It's a trip through the satire begotten by the first movie: a Detroit splintered between poverty and greed, relentless crime and a corporate-controlled police dep, between human and cyborg (which prove to be the same).

As the movie, Rogue City begins with a satire of news and crime, a message from the corporation which runs Detroit police, the news station taken over by criminal punks.

It channels the spirit of its cinematic source - critiquing society, the way consumerism monetizes tragedy, and itself. It points out societal issues, but works alongside to deliver a product which must succeed commercially.

In accordance with the movies and pure action games, the punks understand only one language. Robocop arrives at the scene to "negotiate".

Ghost in the shell

Lots of design and writing support Murphy's humanity: as in the movie, he has a close friendship with his partner, Lewis; psychiatric evaluations through the story, kept short, are intriguing and reveal Murphy's relationship with his old and new self; a fair amount of choice oversees the gameplay. We get leeway to express ourselves via Murphy's personality and influence the plot.

Between the shooting galleries of the game and movie, it may be trite to worry about Murphy's feelings and his condition as a human trapped in mobile armor. But the critique of dehumanization via lack of consent and corporate control of law justifies the game's intent to offer choice in humanizing Murphy.

One obvious question about Robocop is the viability of having something that may be non-human patrol the streets and represent the law. The matter is complicated because by basic observation, Murphy is human. Other people see him with skepticism and fear, but two checks to pacify his behavior: a programmed directive to protect civies, and his own humanity.

*

Rogue City applies this elegantly by not allowing Murphy to attack civilians, a point which works twice: gameplay resources are freed for other mechanics, and Murphy would never hurt innocents.

There's another recourse to compassion, less comfortable. Sometimes, when friendlies talk to Murphy they allude to his condition in a passive-aggressive manner, treating him as a person but cracking a rude joke.

It's intentional, and good writing: even if his allies see Murphy as a person, they might be anxious around him. It's a natural slip about the unease of facing a person transformed into a cyborg law enforcer. Murphy reacts to the remarks humanely, which makes him likeable, worthy of understanding.

*

It's supposed to be uncomfortable, a cyberpunk trope about life transformed into something mechanical, a tool that may or may not be human. When Murphy says "It does not hurt - physically," it's easy to dismiss it as acknowledgement about his health. But we don't know if somewhere deep he is hurting because of the life he lost.

That past life bubbles to the surface in scenes where Murphy hears bits from before the murder - his family calling, voices which deny his humanity, a glitch of empathy fused into the new form. Murphy even remarks how OCP, the corp that made Robocop, sees the memory "glitches" as obstacles.

Granted, some flashbacks overstay their welcome by forcing Murphy through labyrinths of memories, assaulted by doubts. The scenes make sense and fit the array of humanizing him, but may be tedious as gameplay and would've worked better by being shorter. There's only so much you can accomplish by reliving trauma.

*

Robocop will not settle questions about consciousness and humanity, but that's also not his purpose. His actions are his own, and here, the player's. They cannot supply revelations beyond what you already know about Robocop. But they're a motivating companion on the road to justice, and the hallucination scenes are a stark reminder of what once was.

Memorable moments which keep the pacing and motivation between action and downtime abound: terrorizing a suspect by destroying his prized possessions; chatting with the psychologist about identity, loss and purpose; helping bring a kid home while his dad is missing; encouraging a young cop on his progress. Not required for a Robocop game, but welcome and done well, bringing depth to what could have been a simple shooting gallery.

The side-goals give Detroit dimension as a run-down city, humanize Murphy and provide extra experience. The only quirk is how the game conditions you to stumble into every corner in search of evidence - misc objects which add no depth, minus bits of experience, the game's attempt to pad its time.

Pulpy satire

Like all fiction, games are suited for 'dystopian romanticism' - the intrigue of exploring hostile environments, finding their quirks and solving their problems.

It works for action games as means for immersion into cyberpunk society, a combo of reality and exaggerated satire. Pulp satire is the proper way to insert drama into action games, because the dissonance between gameplay and theme decreases.

In other games you're told you're a hero while mowing down thousands of enemies - here, you're the bloody arm of the law, ruled by human reasoning and empathy where applicable.

*

The pulp puzzle fits almost flawlessly: the criminals are irredeemable, the main villains are believable satires, technology has created Robocop - a cop with consciousness - but also killer robots controlled by those in power.

Greed and poverty are ever-present - the game holds a bias about people seeking the "comforts" of prison thanks to its advantage over sleeping on the street. The notion is absurdist but no less real, fit for a poverty-stricken city ruled by profit.

Pulp violence can be unsettling when done as spectacle meant to shock. The Robocop series uses it so, and to deliver a basic critique built on modern anxiety - Detroit has fallen to criminal gangs, one of which has tortured and murdered Murphy. Thus, Robocop has no time for due process, helping reduce the funds needed to run the police force.

*

Regardless of preferences and the strength of their critique, action games are often commercial products. Like others, Rogue City bumps the dissonance between themes and gameplay - the movie wants to criticize violence but also glorifies it, becoming a commercial success. As an action game, Rogue City does likewise: it's a satire of violence, greed and dehumanization, but also a fine brutal game.

If you value the first movie's commentary on violence, greed, and what it means to be human you'll find it here. Otherwise, a game staying true to the movies will likely not surpass them in moral complexity, unless it chooses a different protagonist. Robocop is a conscientious officer, bent on protecting the innocent - but he's also a law enforcer, and treats the guilty with extreme prejudice.

Like the movie, Rogue City is limited in the ability to criticize due to its nature as stimulant. The movie satirizes Hollywood but has to churn out profit. The game can poke its own industry with limited scope - it's a fine specimen of action and a pun on itself.

Robocop on duty

Murphy is imbued with surprising physicality. He can sprint, dash, toss objects at his enemies or grab them by the throat and launch them into their friends. He can focus his reflexes (slow motion) to deal with motor gangs, then slam their motorcycles back. The game understands the importance and joy of physicality, something which game design should aspire to.

By the end, playing as Robocop is suspiciously fun thanks to agile mechanics. With Indiana Jones it was more facile to accept lateral design (exploration and stealth) because you expect them in an adventure game where the protagonist is not the Doom Slayer.

Here, the integration of imm-sim elements is commendable thanks to the life they infuse into Robocop, how they give dimension to an action game and how well-paced everything is.

*

It's a pleasure to engage with dystopian Detroit, in as much as we enjoy simulating dangerous situations to gain knowledge from them. Or to enjoy the stimulation of simulated violence.

One disappointing quirk is the lack of more complex detective work. Murphy is not suited to be a private-eye and his goals are often resolved in a linear manner - not much recourse to thinking on the player's part, and everything handled by game mechanics like visual analysis.

Accessibility options like objective markers are great, but they should be optional and supported by natural means: characters pointing relevant locations, the player deciding the course of an investigation without explicit guidance.

By contrast, the other "Robocop-like" game, Deus Ex, has more freedom in narrative branching. DX is suited to branching design because it uses multiple ways to progress: action, exploration, stealth, hacking, social. Mankind Divided packs one of the best detective quests in gaming - a case where you investigate properly, with multiple means, and can accuse the wrong suspect.

A Robocop game doesn't require relying too much on the player's mental skills to be enjoyable. But when everything is handled linearly and guided by objective markers it does diminish the freedom of investigation, personal achievement and mental feats other games can offer.

*

Rogue City could be called a lite immersive sim. Like Indiana Jones and The Great Circle, it borrows features from imm-sims and simplifies them enough to not distract from action.

For the sake of brevity, we'll say an immersive sim is a game with basic simulation and progression elements, inspired by lateral design and RPGs (which could actually be defined in the same way). Lateral design means you have multiple progression paths, or that different mechanics have multiple applications.

Rogue City translates this into non-mandatory exploration scenes and goals, which may sometimes be done in more than one way. Fans of Deus Ex, Dishonored and Prey (and a bit of Crysis) will recognize their DNA, edited to support the action imperative.

Time to praise writing

It's a surprise to say that writing can carry Robocop, but dialogue does heavy lifting in this action game. Nothing special at first glance, except it is special through its naturalism. It expertly uses the street slang of the movie, sweetened with Murphy's quotable replies.

Being faithful to the movie's writing makes Murphy sound like himself, makes punks be cannon fodder caricatures, and upholds cyberpunk Detroit as action playground and cautionary tale.

Like the movie, Rogue City understands how its villains are believable caricatures of greed. It makes it easy to want to hunt down the believable one, and pity and be annoyed by the caricature.

In the end, it's impressive how so much work has been put into humanizing Murphy. It speaks to the qualities of its developers, and a welcome example of maturity from an industry which tries to understand the importance of writing.

This is the benchmark for future Robocop games, evolved from the first movie's DNA: violence augmented with agility, leeway in shaping Murphy's personality, and the possibility to realize he's still human.

Game design lessons

Inspiration from the source

Respecting the source material is not always needed. You can sometimes ignore it with strong writing and gameplay. But Rogue City gets the first movie right, in every way which matters: action, satire, humanity.

Building relationships

Action is king - or law enforcer, i guess - but Rogue City spreads out encounters with people to create dimension and memorable relationships.

Murphy also gets to be a mentor to a young cop via constant communication in some missions, or hunting leads in others.

Conversations are kept short, spread through the story, building relationships while judging criminals.

Minimalist lateral design - narrative and mechanical

Robocop can use abilities which match his condition, or serve gameplay. Sprint, dash, ram through walls, use criminals as projectiles, heal from power boxes, leap from heights, send motorcycles flying.

Immersive sim or not, more complex mechanics - exploration, social design, branching stories - are simplified to maintain action pacing.

Naturalist writing

The game borrows the exact language of the movie with eerie fidelity. It uses street slang - not always pulp - to fit Robocop's world and elevate the game beyond a shooting gallery.

Tossing is fun

Grab enemies and slam them into the environment or each other - simple, effective, fun. Other games know this, but not enough, though Crysis showed the merits of the mechanic a long while ago.