From human to cyborg to post-human - Ghost in the Shell and Ghost in the Shell: Innocence (also, transhumanism)

Human evolution one cyborg at a time.

Ghost in the Shell feels like futurist Renaissance. The title intro sequence shows the creation of the self-aware cyborg - first, engineer her mind then shape her body in graceful transitions. Plus the classic anime fixation on her breasts.

A moving sketch devised by Renaissance painters and engineers, a sequence of stylized concepts about how the 1990s would imagine the creation of the cyborg. It’s intriguing and unsettling, the human body reconstructed from the inside-out, stronger and sexually pleasant.

Wholesome level: Dependent on how you enjoy cyborgs. Good if you want entities capable of empathy to gain self-awareness.

The moment of ‘coming back to life’ after the intro is one of distance and potential loneliness: Motoko wakes up in the dark cocoon of her room, contrasted against the light which envelops the city. (Funnily enough, the visual portrayal implies she needs no shower before dressing up, but this may be a case of brevity in visual design.)

We may think the urban glow provides safety, a benevolent newness for the loneliness of the newly-minted life, but this is cyberpunk. The city is a vertical and horizontal labyrinth, an oppressive structure of concrete, steel, poor neighborhoods and market encampments adorned with varicolored ads.

As all good fantasy, the city of the nigh-dystopia if a character itself, beautified with the mix of traditional culture and futurist interpretation carried on the transportation means of the present. In cyberpunk the city is rarely a space for healing, but Motoko moves through it in body and mind to achieve greater freedom.

*

Cyborg is as cyborg does so GITS spends a long while to shape Motoko into a technology-enhanced martial-arts cop driven by reasoning. She is tactically-smart, her body is designed with ports for direct connection with the information matrix of the police. More expansive than ours, her mind becomes the city, able to access its labyrinth and secrets at will.

It’s after the somewhat long-winded action-blast that GITS becomes itself. It asks questions which, easy to see, will become relevant for Motoko: birth origin, memories of loved ones, childhood. Major’s ‘Do you even know who you are?’ rings true because memories and experience comprise our identity, and the thought of living without memories - at least innocent ones like childhood - may induce existential dread.

This is a future where humans can be hacked. The parallel between computers or storage devices and the human mind is old in modern media. But in the age of information it’s more palatable with the advent of neural interfaces between the brain and various gadgets.

A character finds out his recent memories have been programmed into his mind. ‘But that can’t be’ is the natural response, as realizing your memories are false is like waking up in a nightmare, possibly void of identity.

Questions follow: the reality of memories and the experience they carry, how they shape who we are, how much our experience is formed by physical processes in the brain. Like humans, the cyborg hopes to find itself via the scientific understanding of its mind while the nature of the soul, were there to be one, remains elusive.

Following this bit of knowledge, we see Motoko be born again: she floats underwater to live the gentle experience before birth, before facing the world. She approaches the surface and when she meets herself, her reflection, the illusion breaks and the material world appears.

No matter how advanced or unsettling, technology is a natural extension of the mind, a step forward in expressing man’s need to adapt or overcome nature. The distance between the stone wheel and the microchip brain implant is great, but both are facets of our need to understand and optimize our existence.

‘Not long ago, this was science-fiction,’ Motoko says while listing the benefits of the cyborg body. Meanwhile, the police and the state own the cyborg, his or her enhancements and brain. ‘There wouldn’t be much left after that,’ - we don’t know entirely where the line between human and cyborg is drawn and how important the features of the first are for the identity of the second.

“There are countless ingredients that make up the human body and mind. Like all the components that make up me as an individual with my own personality.”The discussion is complicated because Motoko looks, thinks and seems to empathize as a human. At the moment when augmentation is indistinguishable from the human experience, anti-arguments against the cyborg may fall without a logic strong enough to dismiss this new creature as a person, apart from biological essentialism. Unique thoughts and memories, the sense of her own destiny, the ability for meta-cognition (awareness of one’s thoughts) and self-reflection - thus the cyborg makes its case for being a person.

“All of that blends to create a mixture that forms me and gives rise to my conscience.”Still, Motoko somewhat contradicts this tenet of humanity by saying she feels confined, only free to expand herself within boundaries. But this understanding is as human as it gets - we are free to expand ourselves and our knowledge within the boundaries of the human mind. She also seeks a sort of forgetfulness, wistfulness at the bottom of the ocean, as her partner seeks the same in drinking.

The question of finding the ‘ghost’, a representative of the soul, comes through another cyborg. Major’s partners are trying to find the ghost via scientific means, unpacking the programming which made the cyborg behave in chaotic ways. While the data is there, the ‘proof’ of a soul lingers even with complete scientific and tech analysis.

To be fair, this confusion remains intentional - regardless how much we unpack the human mind and find its deepest secrets via neurology, science and medicine, the question of a soul will remain perpetual. By understanding what the soul is we only get more questions about its origin. Whether the soul is material or supranatural, we have to inquire about its programming, purpose and creator.

“DNA is nothing more than a program designed to preserve itself. Life has become more complex in the overwhelming sea of information. And life, when organized into species, relies upon genes to be its memory system. Man is an individual only because of his intangible memory - and memory cannot be defined but it defines mankind.“This is how another cyborg declares itself a sentient entity. Its counter-argument for humans denying its personhood is the question of objective proof for existence and life (and implicitly consciousness). We have subjective proof of our own self-awareness but have difficulty defining life via consciousness in objective terms. Thus, we may accept the new form’s argument for life and self-awareness in its own words: ‘I am a living, thinking entity who was created in the sea of information.’

In the great tradition of villains meeting their heroes, Motoko and the puppet-master find each other in a battle of the minds. An intimate communion where one mind overtakes the other and seeks the unbounded unification of identities into the universal. The same principle of joining with a universal mind, consciousness, love which we know from various philosophies.

Part of how the ‘villain’ gained awareness was through complexity, engulfed in streams of information. As expected, the creators saw his self-awareness as a glitch and attempted to isolate him in one body, not in Eden but in dystopia.

*

As the movie predicted for Motoko, the ‘villain’ justifies his appeal to independence through self-sentience and meta-cognition, observing his own existence. The argument applies to Motoko’s personhood, made more explicit by taking over her body and using her mouth to speak.

As all self-aware intelligence, the other cyborg seeks reproduction, but at the expense of Motoko’s identity. Finally, the admittance that both experience the same condition of the self-aware man-made life-form.

But though Motoko fears losing her identity, the other seems prepared to ‘evolve’, to be part of a universal consciousness in the matrix of information, ignoring Motoko’s anxiety about his plans.

This all feels strangely familiar, human-like. It’s the path of consciousness to earn for universal understanding, for union with total awareness. Or perhaps the limit of human understanding makes us think so, and the cyborg mimics our own programming.

A bit suddenly, the happy-end rushes in. Motoko is now in the body of a Gothic Lolita - obviously - has newfound wisdom, and access to both the digital and the physical realm. She keeps her own identity but stands at the edge between the infinite and the individual, between human experience and universal consciousness, aided by the ever-growing digital matrix.

The writing front is just about purely functional. The script affords not much space for metaphor and lyricism, most everything is stated plainly via expository dialogue. Characters will sometimes gather to state something they should already know or to spell emotions which may be obvious from the mise-en-scene.

Purely-functional writing is standard fare for anime and cinema overall, but explicit exposition in dialogue can detract from the enjoyment of understanding characters and how they discover their world.

Ghost in the Shell is the kind of movie which may be easily translated into essays because of how plainly it states its thesis and arguments. There’s always more to discuss of its ideas, but the script delivers as much as reasonably possible while constructing a story around its exposition. Like wining and dining, I prefer a bit of metaphor in dialogue, more mystery and less exposition, but the visuals provide the symbolism to let the prose be explicit.

GITS is less aesthetically pleasing, color-wise. It’s equipped with muted colors, the leaden-like city and the anxiety-inducing rusty sky. Neon-inspired coloring and lighting are ever-present in modern times for good reason - strong colors and gradients, sometimes complimentary, induce a dreamy state and a place of respite among the darkness of the urban night and its perils.

The 90s, following along from, well, the 80, had less time to enjoy the latter’s aesthetics in the attempt to paint their own visual identity. No surprise how the 90s continued the aesthetics of dystopia but stripped it of charm, with less neon and more unfriendly colors. (For a logical conclusion to modern fears see the overlap of aesthetics in Blade Runner 2049, where neon is present but muddled with climate change-induced darkness and mountains of human-produced waste.)

Innocence

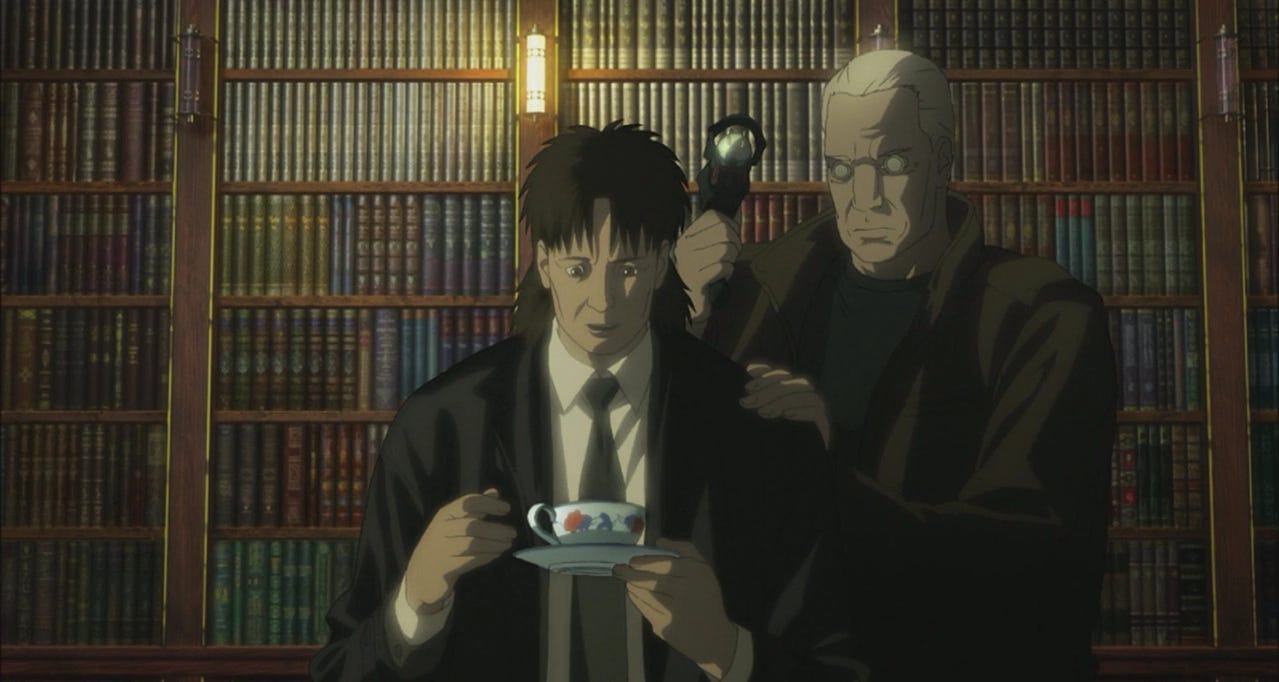

Innocence is the more cryptic version of Ghost in the Shell the first.

Why Androids are made in the image of their creators - humans - is a good question.

Some obvious answers are:

Familiarity - create something or someone around which we feel safe

Mechanical, kinetic, physical benefits - the human body is agile enough and has a proper form to support mobility

Limited knowledge - we are bound by the human condition and cannot create something beyond its imagination.

‘A beautiful puppet is just soulless flesh.’We return to the ‘source’ of investigation - the question of consciousness, the nature of the potential soul and our relationship with new forms of intelligence.

Ghost in the Shell cannot end the discussion because their nature remains elusive. Once you define the soul the question of its creation rises to complicate the matter endlessly. If consciousness is more than a biological impression than it may be a universal phenomenon and be as valid for post-human entities as it for us.

It’s the same celebration of cyberpunk, with one step beyond its limitations. On the post-cyberpunk flipside, there may be nowhere else to go. Batou is already human for all intents and purposes; Motoko evolves no further than she did previously, but her awareness is both personal and universal, connected to the expanding matrix which envelops material reality.

Cyborgs may be better than humans at certain feats, but without greater understanding they remain machines. A creature may look alive, but it’s difficult to understand the degree of its self-awareness as it mimics human understanding.

The cyborg appears real, human, it speaks as if self-aware and makes the case for its survival. As all technology, the cyborg is an extension of humanity but one which may eventually become aware of its condition, its relationship with humans and the world.

Intelligence and awareness being self-reinforcing may apply to both human and non-human, post-human and thus cyborg. But the question reverts to the subjectivity of self-awareness and the difficulty to establish where it is valid. Humans have a degree of meta-cognition part of the reinforcing mechanism of understanding. If the non-human intelligence shows the same ability it may be recognized to have achieved consciousness.

‘Humans are nothing but the thread from which the dream of life is woven. Dreams, consciousness, ghosts are rifts and warps in the uniform weave of the matrix.’The post-human may hallucinate, dream, imagine on its own terms. The human mind has its own physical mechanism which stores impressions - the post-human likewise has its own means to store and interpret experience, and it’s difficult to declare if the former’s is more meaningful than ours.

‘There are as many paths to proving your existence as there are ghosts.’Thus the story makes its logical point for subjective self-awareness and the potential of the soul.

Innocence has no Motoko for a long while. Batou is cool and a cyborg taking care of a charming hound, but still less intriguing than Motoko. If he deals with the same doubts and questions about identity and humanity as Motoko, he shows it less. It’s good that he avoids philosophical verbiage because Motoko already played the role, but this made her more interesting - and she was the star of GITS - and to compensate, his new partner fills in for Batou’s quietude.

‘The essence of existence is the genetic transmission of information. Society and culture are enormous memory storage systems. Cities are huge external memory devices.’Like GITS the first, Innocence upholds visual storytelling. The script devotes a whole mid-section to a stylish presentation of the second major location: a visual-only celebration adorned with the Japanese choir of the first movie, people and cyborgs brought together to mix and remix tradition into the steel and concrete labyrinth, potentially unaware of a better place but glad to engage in such a human act of respite.

Part of the cyberpunk cosmos, the new city appears inhumane at first, built not necessarily to accustom humans but to provide a minimum of comfort and nest endless digital networks. A meld of industrial, traditional and futuristic, the new city imposes itself as its own organism, growing and covering the sky. In the labyrinth made by haphazard living spaces, people and cyborgs mimic the life remembered from other cities.

Fans of Deus Ex: Mankind Divided will recognize the inspiration for Golem City, the amalgam of industrial spires forced on its inhabitants as living spaces.

In the end, the story reaches a logical conclusion: the element which makes the cyborg desirable is an infusion of humane intelligence or ghost. This hybrid of human and machine exists alongside the self-aware cyborg, but they can manifest different preferences, turn against their creators or be indistinguishable from humans in behavior.

This is no cop-out but human understanding of awareness, empathy, consciousness. The post-human may go beyond and evolve into greater consciousness but this may be forever remote to the human mind.

The movie’s attempts at placing the post-human alongside human understanding remains timid. Whatever knowledge we gain was already present in GITS 1 via Motoko’s musings and ‘evolution’ beyond the personal, the individuated. But this quirk is less criticism than state of being - we sympathize with Motoko and Batou, we understand how consciousness, illusion or not, may not be limited to humans. And thus the point of empathy is made.